Have you noticed that you are staring at people more often? On my outing to the supermarket yesterday, I sensed that social conventions on staring seemed suspended. Browsing the shelves at a distance, I saw people looking at me intently, and, of course, I was doing exactly the same. None of this staring seemed threatening, more of a relaxed: check this person out, focused looks replacing the usual, awkward British muttered ‘sorry,’ if I accidentally got too close. After a while, I found I began moving out of the way automatically and even anticipating when someone was about to appear in an aisle.

We know instinctively that staring at someone from behind can make them turn around and many of us have had the experience of thinking about someone only to have them text or call. African bush hunters are known to be able to communicate over vast distances, starting supper preparations back at the home fires, long before they appear with their haul of fresh meat. Could it be that in these socially estranged times, communicating from a distance is an ancient element of our human experience that is now usefully coming into play?

Being more in tune with their senses, animals make use of stares more frequently than we do. I’ll never forget the time Dragonfly stared at me as I left the yard, forgetting to let the ponies out of their stables. The intensity of his gaze stopped me in my tracks and gave me time to remember what I needed to do. If I spend too long on the laptop, Rosie will stare at me to let me know my time is up. No matter what time of day I arrive, the horses seem to know when I’m coming and will magically appear at the gate when I walk quietly down the track to their meadow.

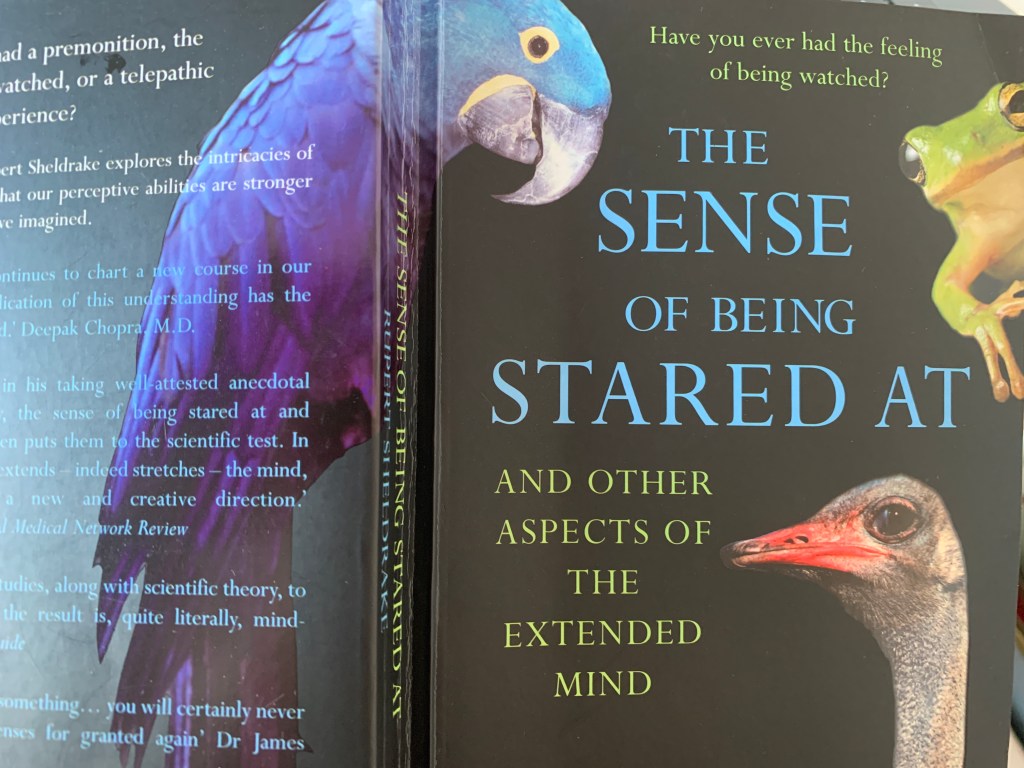

Deer and many other herd animals are extremely perceptive at reading intentions. In his illuminating book The Sense of Being Stared At, Rupert Sheldrake shares examples from hunters and wildlife photographers, who know to keep their eyes averted from the ones they intend to capture. One old and very stiff horse I knew gave his owner the run-around for years. It amused me to watch this horse change from sedentary old man to sprightly colt the minute he saw this person come to get him in. Apart from making his owner swear a lot, his other favourite game was to taunt Sheranni by dropping a single pony nut from his feed bowl into the deep groove in the grille separating his space and then step back and stare as the young horse tied his tongue in knots trying to reach it.

As a biologist, Sheldrake is interested in studying the idea of mind as an extension of the brain rather than being contained within it. His case studies exploring what he names ‘the seventh sense’ include a detailed study of a parrot who was recorded speaking 7,000 different sentences and who had an uncanny ability to know and name what his human was thinking and doing even when she was in another room. These studies make for fascinating reading, inspiring a broader view of animal nature and human nature.

“If the seventh sense is real, it points to a wider view of minds – a literally wider view in which minds stretch out into the world around bodies. And not just human bodies, but the bodies of non-human animals, too…our minds are extended into the world around us, linking us to everything we see.”

The Sense of Being Stared at and Other Aspects of the Extended Mind. Rupert Sheldrake. (2003)

This intriguing idea of stretchy minds seems particularly relevant now as we prepare for weeks of living apart from most of the human race. It could be that our survival depends on realising that although we are physically separate we are linked in mind. That might sound scary to some, imagining the thought police hovering over your car as you idly consider making a non-essential journey. Reassuringly, Sheldrake reminds us that most seventh sense conversations are between people who are already close.

With many people now living with a cat or dog for company, conversations between humans and animals have never been more important. The daily dog walk is no longer routine, but a focal point of the day. I know that I’m anticipating my daily walks with an excitement that is eagerly shared. Animals must live with our moods, whether it’s joy, fear or sadness. They read our emotions with a sensitivity that can remind us to soften our sorely worried hearts. None of us know what will happen next in our human world, but knowing our animals are safely by our side is especially comforting at this time.

Surprise! Captured during a group session last summer: the very moment I shared my feelings of appreciation for my horse, he arrived from the far end of the field as if I’d called him.