What the horse knows: Life Lesson No 8

‘Animals know this world in a way we never will.’ The Irish poet and philosopher John O’Donohue’s words are filled with simple wonder. He contrasts the deep quiet of the animal world with the distracted world of humans drawn by the lure of bright windows.

It’s true our world is colourful in comparison with the subdued natural world. We love novelty and change and noise. We lose ourselves in excitement. Sometimes it’s hard to slip away from the fairground and come back down to earth. We resist because doing nothing alarms us and makes us feel that we are nothing. Our restless screen-filled lives make it easy to be preoccupied. We forget that behind the demands of our do-lists there is a deeper purpose. Yet within our conflict we want our lives to mean something more than more things to worry about.

The horses remind us to listen. They remind us to move out of our worry-minds and into the unhurried world. It’s easy to forget that the world as we know it is not the only world. There is the grass world, the sky world, the bird world. There is the whole world from a million points of view, none of them ours. Observing the horses at rest, a spaciousness emerges from the rhythm of their breathing. When they are all together, they breathe in time and their breathing draws them closer. Being with them like this is more than merely relaxing; it feels like a invitation to wake up from a dream.

Our mesmerising thoughts take us away from the world of animal being, of sky and grass and bird. Forgetting we are animal, we dwell in a dreamscape of our own making. In our shadow world, we get obsessed with the things people say or do or think. We believe the worst because, somehow, it helps us to feel safe. When we’ve had enough of our own loopy thinking, we start to wonder how we might clear out some of these negative thoughts. Believing that we need to manage them, tidy them up, we file them into neatly labelled boxes, or drive them away with drink or drugs. We wonder why they always come back. We wish we could escape our own dullness.

We can learn from the animals. For them, brightness is already there. As Plato observes, there is light outside the cave of ordinary ignorance and superstition. There is knowledge beyond going through the motions and living life on auto-pilot. There is clear sky. It begins in wonder. All life begins in wonder. The horses know this, of course. Their lives might seem dull. They might look routine to us, but that is because habitually as predators we scan the surface for anything useful to us. We are fast fish on a feeding frenzy.

Truly bright living requires us to swim up to the surface and take a good long breath. And then a good long look.

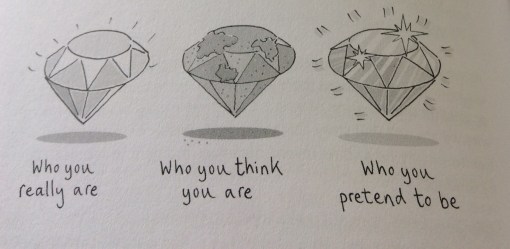

Horses value what is most clear in us. The beauty of working with horses who see beyond our insecurities and anxieties is their ability to point out how light and sparkling we can all be, if we could just drop the pretence.

Horses value what is most clear in us. The beauty of working with horses who see beyond our insecurities and anxieties is their ability to point out how light and sparkling we can all be, if we could just drop the pretence.

Tinker: learning work.

Tinker: learning work.